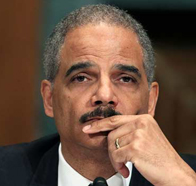

Attorney General Eric Holder sent out a memo to Justice Department employees Friday (available here) saying he transferred $150 million from DOJ’s funds to the Bureau of Prisons to avoid mass furloughs of prison guards and staffers.

Absent this intervention, we faced the need to furlough 3,570 staff each day from the federal prisons around the country. The loss of these correctional officers and other staff who supervise the 176,000 prisoners at 119 institutions would have created serious threats to the lives and safety of our staff, inmates, and the public.

The Department’s actions can protect BOP’s facilities only through the end of the fiscal year in September and these actions do not address the serious life and safety issues that the BOP faces next year under continued funding at the post-sequestration levels.

Sequestration requires a $338 million cut in BOP’s budget, of which $330 million is for salaries. (That still leave it with 95% of its budget.) Under the sequestration plan, a guard would lose one day of paid work every fourteen days. From Holder’s February 1 letter to Congress about the sequestration cuts:

The sequestration would cut $338 million from BOP’s current budget. BOP would face a furlough of nearly 36,700 on board staff for an average of 12 days, plus curtailment of future hiring, if sequestration occurs. This equates to about a 5 percent reduction in on board staff levels and would endanger the safety of staff and over 218,000 inmates. As a consequence, BOP would need to implement full or partial lockdowns and significantly reduce inmate reentry and training programs.

I’m not sure giving guards an extra day off every two weeks without pay is as big a calamity as portrayed by Holder. More troubling to me, and less widely reported, are the cuts in rehabilitation and vocational programs. Cutting these programs is likely to result in increased recidivism. Inmates who leave prison with skill sets and having undergone substance abuse treatment are more likely to turn their lives around and avoid a return to prison. Cutting these programs will also give the inmates even more dead time than they have now, which in turn is likely to lead to increased behavioral problems, making the prison guards’ jobs more dangerous. As Holder also wrote in his February 1 letter to Congress about the sequestration cuts:

This would leave inmates idle, increasing the likelihood of inmate misconduct, violence, and other risks to correctional workers and inmates. Further, limiting or eliminating inmate programs such as drug treatment and vocational education would, in fact, lead to higher costs to taxpayers and communities in the long run as the lack of such inmate re-entry training makes it less likely that released inmates will be successful at reintegration into society upon their release.

The furloughs would also likely mean a cut-back in inmate work hours, since there would be fewer guards on duty to supervise them. That will mean a reduction in their earnings going to child support and restitution.

Unanswered as yet? What cuts are coming to inmate mental health services? Why can’t we at least send the 86 detainees cleared for release at Guantanamo back to their home countries? While the Pentagon bears the cost for housing them, the Administration just requested an additional $49 million for Guantanamo.

So furloughs are a lousy idea. But there are many other ways for the Bureau of Prisons to save money. The U.S. has become a global jailer. We should return the inmates we kidnapped from Africa, South America, Mexico and the Middle East. They are costing us a fortune and many have not committed any crime in or against the U.S. Examples: The Somali pirates tried and sentenced to life in prison; extradited FARC and cartel members, many of whom are serving double-digit or life sentences; Viktor Bout set up by informants in Thailand over a deal to buy planes that fell though. DEA agents kidnapped him, lost their first extradition battle and the U.S. appealed, spending even more money. Bout was also kept in segregation at MCC New York, at extra cost. What do we get for it? A bill for that will amount to around a half million dollars to lock him up in a maximum security prison in Marion, IL, for 20 years, after which he will put on a plane to Russ1a.

There’s also Russian pilot Yuri Konstantin Yaroshenko, and his co-defendant, set up by informants in Africa, extradited here, tried and sentenced to 20 years. (If someone is sending drugs from South America to Africa, with Europe as the final destination, why are we punishing them here? Does the DEA really need 83 offices around the world?)

As to the Somali pirates, some of whom are teenagers, brought here from the other side of the world, then tried, convicted and sentenced in Virginia’s “rocket docket” district:

Thus, when Somali pirates were charged under piracy laws that date back to the country’s founding, they could be tried in Norfolk because that is where the pirates were first brought after their arrest. Last month, five Somali pirates were convicted in a 2010 attack on the USS Ashland off the coast of Africa; four of the five face automatic life sentences.

The current cost of housing a federal inmate is about $30,000 a year. While BOP won’t say what it costs to house an inmate at the Supermax in Florence, Colorado, state prisons spend about $75,000 per inmate per year. From BOP’s response to an FOIA request by Solitary Watch:

“The BOP does not collect separate or specific data held in Administrative custody or at USP Ad-min Max Florence. These costs are included in the general per capita costs for the applicable facility. Since the prisons at Florence make up a Federal Correctional Complex [which also has maximum, medium, and minimum security inmates], the operating costs are based on all complex operations, shared services and facility expenses at this site.”

While Supermax in Florence has may house only 400 or so inmates, there are about 19,000 federal inmates in some form of segregation in federal prisons, all at an increased cost.

The costs of housing 179,000 inmates is only part of it. We’re also paying huge fees to private prisons to house another 40,000 federal inmates. There’s also the cost of transporting all 219,000 of these prisoners, which is the responsibility of the U.S. Marshal’s Service, also a DOJ agency., and its JPATS program, a step up from Con(vict) Air.

Many are so old they no longer bear any danger to society. They could be released on home monitoring. As could the lesser drug offenders.

Holder shouldn’t look so perplexed. There are other solutions. For an relatively quick fix, Congress could pass the Barber Amendment, increasing good time to federal prisoners.

Barber Amendment – Title 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1) is amended as follows: by striking the number “54″ in the first sentence as it appears and inserting in lieu thereof the number “128″; and in the same sentence, by striking “prisoner’s term of imprisonment” and inserting in lieu thereof “term of sentence imposed”. This Amendment is retroactive.

Other ideas: Congress could pass the recently introduced bill that would give federal judges the authority to sentence below mandatory minimums. Even better, it could repeal mandatory minimum sentencing laws for non-violent offenders. Furloughs aren’t the answer.